"Why do you like blue so much?"

"I don't think I chose blue; I think blue chose me."

I'm not sure when it started, but more and more blue things began appearing in my home. From the clothes I made for us, to the paintings on the walls, and even everyday items. So when he asked, I wasn't surprised, though I couldn’t quite explain why. After a brief pause, I responded with an answer that didn’t quite address the question. Looking back, over the past four or five years, blue has certainly caught my eye more than before, and it has appeared more frequently in my work.

How did I come to like blue so much? As a child, blue didn’t particularly appeal to me more than any other color. Like many kids, I was drawn to bright and colorful things, and it seemed like my "favorite color" changed frequently. It wasn't until I left my hometown and moved to a rainy city that I realized how deeply the clear summer skies of the northwestern China had imprinted on me. Those endless blue skies, day after day, set the perfect stage for a carefree youth, untouched by serious worries.

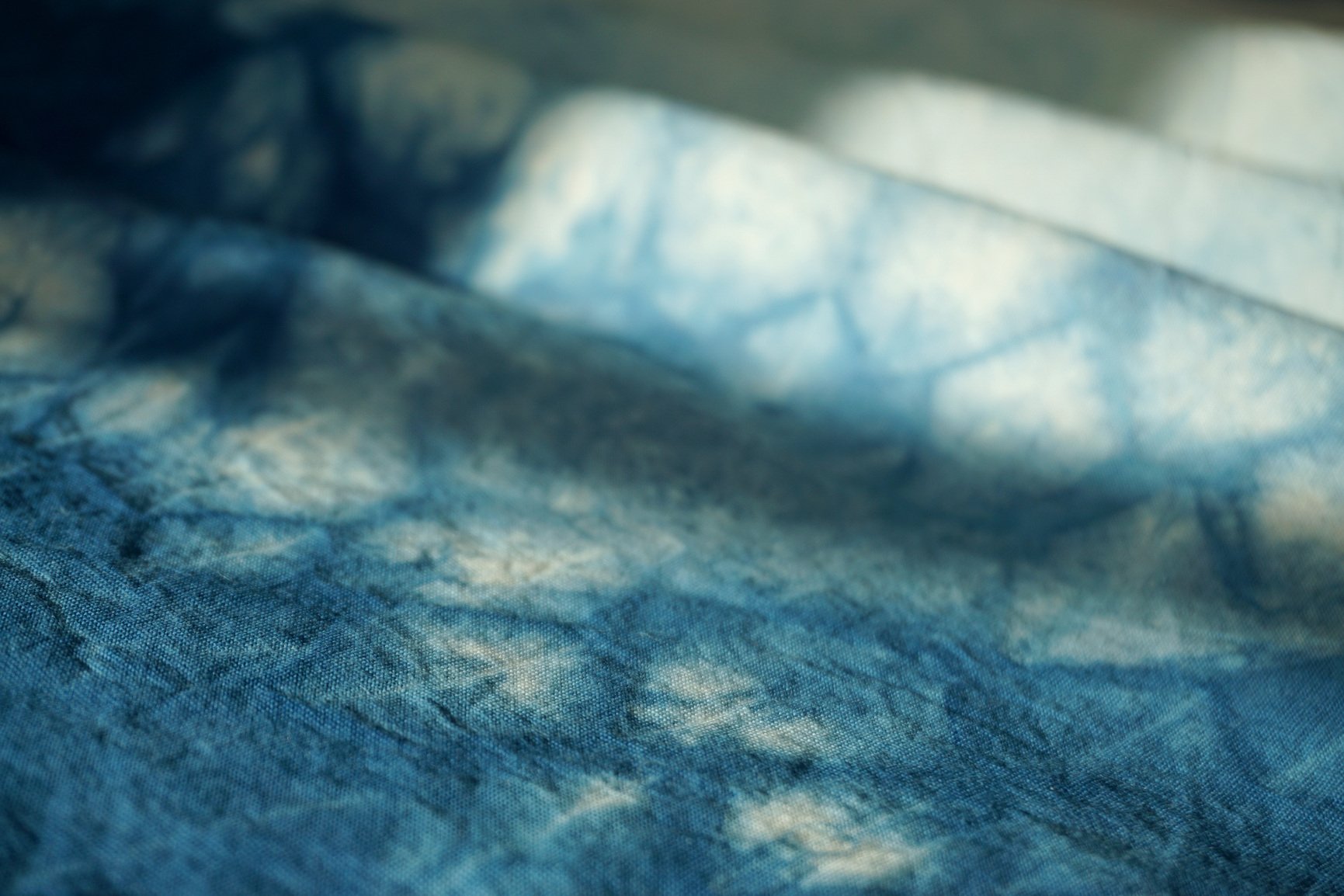

In the winter of 2020, I stumbled upon a blog about natural dyeing and became immediately interested. As someone who has worked with fabrics for many years, making my own fabric on some level had long been on my list. After reading a few books and doing some research, I eagerly started experimenting with plant dyes. However, I didn’t buy any materials for indigo dyeing at the time because its process is more complex than other plant dyes, with many specialized "recipes" that felt overwhelming for a beginner like me. But I always kept indigo dyeing in mind, planning to try it once I had more experience. Many plants can produce earthy tones, yellows, and reds, but only indigo and woad can produce blue. Not only that, indigo dyeing can achieve excellent colorfastness without requiring a mordant. My fascination with it persisted, and I continued to read books on dyeing and shibori, buying handwoven, hand-dyed fabrics from ethnic minorities in southern China, Thailand, and Japan. It's hard not to be moved by these handmade items, crafted with immense time and care. Especially with indigo-dyed fabrics, it felt as if the blue skies and white clouds from my memories were brought to life before my eyes — what a great comfort during the pandemic. After working a lot with these indigo fabrics, in September 2023, I felt an undeniable urge to start indigo dyeing. Maybe it was the end of summer or the distant autumn skies that made it so hard to say goodbye. After thorough research, I chose a base recipe, bought the materials and a large pot, and started my indigo dyeing journey. On a few clear autumn days, I finally achieved an incredibly pure blue:

It's hard to describe the feeling of watching white cotton fabric gradually turn blue through repeated dips in the dye vat and exposure to air, but it's a true healing process. Due to the unique chemical reactions of indigo dyeing, the dye vat itself is a yellow-greenish, almost olive-brown color. So when you first pull the fabric out, it looks quite unimpressive, even a bit unpleasant. But as it slowly oxidizes in the air, a calm blue gradually emerges, like the clearing of clouds to reveal the moon. What struck me the most were the fabrics dyed with Arashi Shibori technique — those undulating patterns, like the sky or the sea, with gentle gradients of blue and white, wrapping around you as if, no matter what you've been through, you could safely sink into them and fall asleep. Later, I turned that precious fabric into a pillow, recreating the candy-shaped pillow from my childhood, which became a comforting presence, wrapping me in warmth during moments of stomach pain.

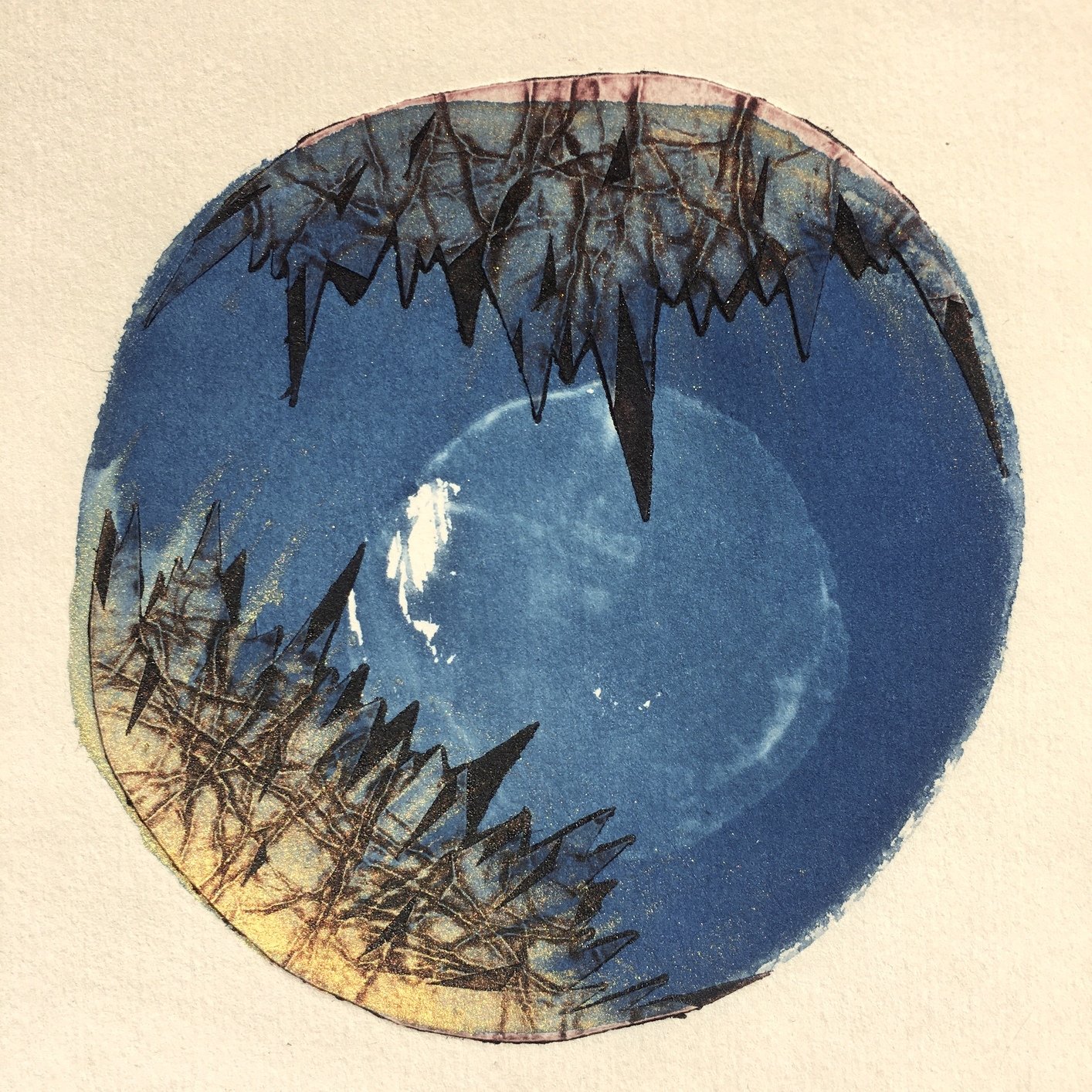

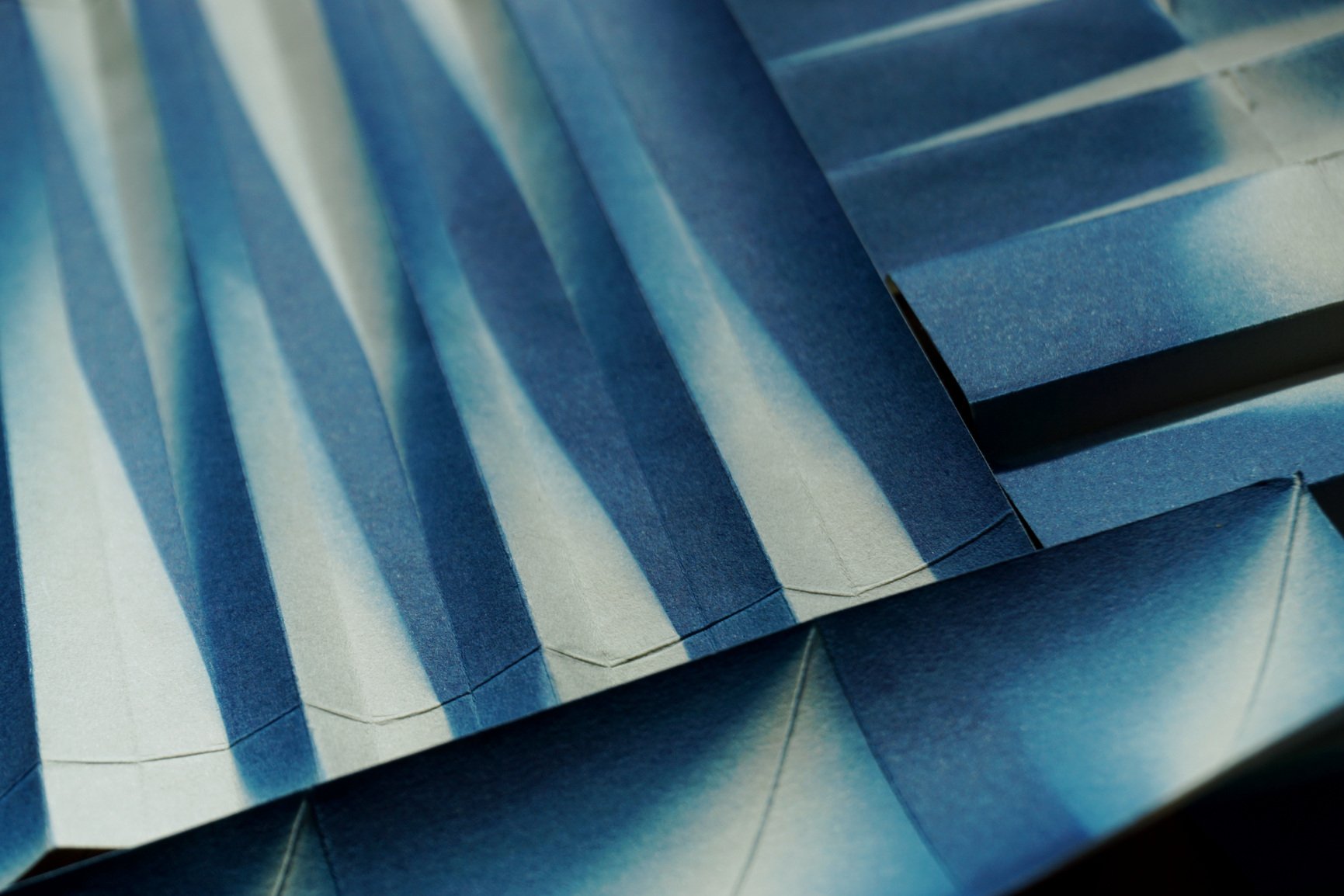

Also in 2023, though earlier in the year, I began experimenting with cyanotypes. One spring day, I happened to see a video titled something like "I Made a Sun-Dyed Dress," featuring a photo of the blogger in a blue dress. Sun-dyed? It sounded interesting, but I had never heard of such a dyeing technique. At the time, I hadn’t yet started indigo dyeing, and I thought this was just another name for it, with a fancy title. Then I knew it was actually cyanotype. The term “sun-dyed” referred to the fact that cyanotype solution needs to be exposed to UV light and then developed through rinsing and oxidation to reveal the blue color. Coincidentally, like indigo, the solution is also in general yellow-greenish. The term "blueprint" actually comes from this process. Although I had known about cyanotypes before, I had never tried them, so seeing the video reignited my interest. For someone like me, who hadn’t yet started indigo dyeing but had long been eager to, cyanotypes were a great substitute. The process is simple, and it’s an easy way to achieve blue on paper. The first simple cyanotype of plant silhouettes that I made is still hanging on my wall, and I’ve continued to explore its possibilities, such as in alternative photography and combining it with harmonograph drawings and printmaking:

Even after a year, every time I watch the unexposed solution wash away, leaving behind a gradually emerging blue, I still feel a sense of wonder. Creating a cyanotype requires sunlight, air, and water — just like growing a plant. Come to think about it, the chemistry behind cyanotypes feels romantic; it’s something lifeless, yet it connects with the universe in its own way, drawing on resources typically needed by living things, then producing something in blue to resonate a little bit with this blue planet. As an artist, I am merely a vessel, a platform for this resonance to occur — with my shape, my warmth, my biases to add a slight harmonic, allowing it to exist in the real physical world as another imperfect yet tangible object.

So perhaps, I never actively chose blue. It came to me, and told me its story; I listened, and chose to pass that story along. It is a color, but also an image, a taste, a sound. Through it, I see the sky and the earth, the ocean and the valleys, the planet, the universe, and myself. I suppose I do like it very much, after all.